Civitas (Citizen), plural Civitates... refers to citizenship in ancient Rome. Roman citizenship was acquired by birth if both

parents were Roman citizens (cives), although one of them, usually the mother, might be a peregrinus ("alien") with connubium (the right to contract a Roman

marriage). Otherwise, citizenship could be granted by the people, later by generals and emperors. By the 3rd century BC the plebeians gained equal voting rights

with the patricians, so that all Roman citizens were enfranchised, but the value of the voting right was related to wealth because the Roman assemblies were

organized by property qualifications. Civitas also included such rights as jus honorum (eligibility for public office) and jus militiae (right of military

service)—though these rights were restricted by property qualifications.

Source: "civitas." Encyclopædia Britannica, Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

With respect to property, the terms freehold, copyhold, soccage,and demesne are useful aside references to property

and voting rights though there are others such as the word villenage (village whose inhabitants are referred to as villein... from which one may derive

the word "villain"), though there are other words which have importance in the present discussion. |

- Freehold:

In English law, ownership of a substantial interest in land held for an indefinite period of time. The term originally designated the owner of an estate

held in free tenure, who possessed, under Magna Carta, the rights of a free man. A freehold estate was distinguished from nonfreehold estates such as copyhold,

tenancy at will, and tenancy for a fixed period, the customary landlord–tenant relationship. Knight service and frankalmoign, which required military and

ceremonial services respectively, and free socage, which involved certain services of husbandry or manual labour, were types of free tenure. (Source: Freehold,

Encyclopedia Britannica.)

- Copyhold:

In English law, a form of landholding defined as a "holding at the will of the lord according to the custom of the manor." Its origin is found in the

occupation by villeins, or nonfreemen, of portions of land belonging to the manor of the feudal lord.

A portion of the manor reserved for the lord was cultivated by labourers who were bound to the land; their service was obligatory, and they could not leave

the manor. They were allowed, however, to cultivate land for their own use. This copyhold was mere occupation at the pleasure of the lord, but in time it grew

into an occupation by right, called villenagium, that was recognized first by custom and later by law. The records of the court baron constituted the title of

the villein tenant to the land held by copy of the court roll (hence the term copyhold); and the customs of the manor recorded therein formed the real property

law applicable to his case. In 1926 all copyhold land became freehold land, though the lords of manors retained mineral and sporting rights. (Source: Copyhold,

Encyclopedia Britannica.)

- Socage:

In feudal English property law, form of land tenure in which the tenant lived on his lord's land and in return rendered to the lord a certain agricultural

service or money rent. At the death of a tenant in socage (or socager), the land went to his heir after a payment to the lord of a sum of money (known as a

relief), which in time became fixed at an amount equal to a year's rent on the land. Socage is to be distinguished from tenure by knight service, in which the

service rendered was of a military nature, although, by statute in 1660, all knight-service tenure became socage tenure. In time, most of the land in England

came to be held in socage tenure. In the United States, lands in the early colonies were given in socage, particularly in Pennsylvania, where the royal charter

given to William Penn created a socage tenure with an annual rent of two beaver skins for the land. After the American Revolution, lands held in socage tenure

from the crown were deemed to be held by the state as sovereign, and several states passed statutes or enacted constitutional provisions abolishing tenure.

(Source: Socage, Encyclopedia Britannica.)

- Demesne:

In English feudal law, that portion of a manor not granted to freehold tenants but either retained by the lord for his own use and occupation or occupied by

his villeins or leasehold tenants. When villein tenure developed into the more secure copyhold and leaseholders became protected against premature eviction, the

"lord's demesne" came to be restricted and usually denoted the lord's house and the park and surrounding lands.

Demesne of the crown, or royal demesne, was that part of the crown lands not granted to feudal tenants but managed by crown stewards until it was later

surrendered to Parliament in return for an annual sum. Ancient demesne was land vested in the crown in 1066, the tenants of such land having a number of

privileges, such as freedom from tolls. (Source: Demesne, Encyclopedia Britannica.)

|

|

Voting Rights in America:

Typically, white, male property owners twenty-one or older could vote. Some colonists not only accepted these restrictions but also opposed broadening the

franchise. Duke University professor Alexander Keyssar wrote in The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States:

At its birth, the United States was not a democratic nation‐far from it. The very word "democracy" had pejorative overtones, summoning up images of

disorder, government by the unfit, even mob rule. In practice, moreover, relatively few of the nation's inhabitants were able to participate in elections:

among the excluded were most African Americans, Native Americans, women, men who had not attained their majority, and white males who did not own land.

John Adams, signer of the Declaration of Independence and later president, wrote in 1776 that no good could come from enfranchising more Americans:

Depend upon it, Sir, it is dangerous to open so fruitful a source of controversy and altercation as would be opened by attempting to alter the qualifications

of voters; there will be no end to it. New claims will arise; women will demand the vote; lads from 12 to 21 will think their rights not enough attended to;

and every man who has not a farthing, will demand an equal voice with any other, in all acts of state. It tends to confound and destroy all distinctions, and

prostrate all ranks to one common level.

Colonial Voting restrictions reflected eighteenth-century English notions about gender, race, prudence, and financial success, as well as vested interest.

Arguments for a white, male-only electorate focused on what the men of the era conceived of as the delicate nature of women and their inability to deal with the

coarse realities of politics, as well as convictions about race and religion. African Americans and Native Americans were excluded, and, at different times and

places, the Protestant majority denied the vote to Catholics and Jews. In some places, propertied women, free blacks, and Native Americans could vote, but those

exceptions were just that. They were not signs of a popular belief in universal suffrage.

Property requirements were widespread. Some colonies required a voter to own a certain amount of land or land of a specified value. Others required personal

property of a certain value, or payment of a certain amount of taxes. Examples from 1763 show the variety of these requirements. Delaware expected voters to

own fifty acres of land or property worth £40. Rhode Island set the limit at land valued at £40 or worth an annual rent of £2. Connecticut

required land worth an annual rent of £2 or livestock worth £40.

Source linking logo:

|

Woman Suffrage:

Women were excluded from voting in ancient Greece and Republican Rome, as well as in the few democracies that had emerged in Europe by the end of the 18th

century. When the franchise was widened, as it was in the United Kingdom in 1832, women continued to be denied all voting rights. The question of women's

voting rights finally became an issue in the 19th century, and the struggle was particularly intense in Great Britain and the United States; but these countries

were not the first to grant women the right to vote, at least not on a national basis. By the early years of the 20th century, women had won the right to vote

in national elections in New Zealand (1893), Australia (1902), Finland (1906), and Norway (1913). In Sweden and the United States they had voting rights in

some local elections.

World War I and its aftermath speeded up the enfranchisement of women in the countries of Europe and elsewhere. In the period 1914–39, women in 28 additional

countries acquired either equal voting rights with men or the right to vote in national elections. These countries included Soviet Russia (1917); Canada (1918);

Germany, Austria, Poland, and Czechoslovakia (1919); the United States and Hungary (1920); Great Britain (1918 and 1928); Burma (now Myanmar; 1922); Ecuador

(1929); South Africa (1930); Brazil, Uruguay, and Thailand (1932); Turkey and Cuba (1934); and the Philippines (1937). In a number of these countries, women

were initially granted the right to vote in municipal or other local elections or perhaps in provincial elections; only later were they granted the vote in

national elections. (Source: "woman suffrage." Encyclopædia Britannica.) |

|

American Civil Rights Act:

(1964), comprehensive U.S. legislation intended to end discrimination based on race, colour, religion, or national origin; it is often called the most

important U.S. law on civil rights since Reconstruction (1865–77).

- Title I of the act guarantees equal voting rights by removing registration requirements and procedures biased against minorities and the underprivileged.

- Title II prohibits segregation or discrimination in places of public accommodation involved in interstate commerce.

- Title VII bans discrimination by trade unions, schools, or employers involved in interstate commerce or doing business with the federal government. The

latter section also applies to discrimination on the basis of sex and established a government agency, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), to

enforce these provisions.

- The act also calls for the desegregation of public schools (Title IV),

- broadens the duties of the Civil Rights Commission (Title V),

- and assures nondiscrimination in the distribution of funds under federally assisted programs (Title VI).

Source: "Civil Rights Act." Encyclopædia Britannica.

|

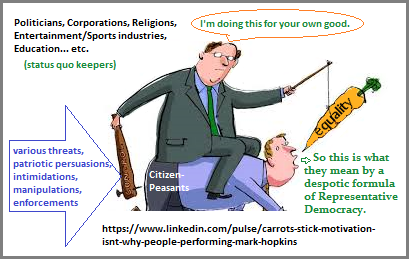

Whereas the "political guild" of yesteryear could diminish potential adversarial circumstances which might cause

them to become a minority and no longer hold the majority opinion or political clout by keeping large swaths of people from voting based on property valuations,

gender, race or age... the lack of such means to control the popular vote could none-the-less be supported by the provision of an Electoral College and

gerrymandering (dividing a voting area so as to give your own party an unfair advantage: Wordweb dictionary). This ability to control the popular vote so as

to diminish its effectiveness, thus as a deliberate intention to circumvent the process of a democracy based on the tenet "a government of, by, and for the

people", is also enabled by an elections and voting system which is rigged and corrupted to serve the purposes of those who are already a part of the

"political guild" that limit their memberships to only like-minded advocates. In other words, though a majority of the people have acquired the ability to

vote, they can only cast their vote for those who will maintain the present system of government and not seek to instigate broad programs of restructuring

which would increase a level of fairness that would give present socio-political ideas a significant challenge to their dominance. A person's vote carries

little power if it is not enabled to bring about significant government structure reforms instead of simply replacing one type of office manager with another

one who may have necessary vision, intelligence, wisdom nor personal wherewithal to bring about comprehensive reforms in the overall and underlying structure

of government. |

Peasant: any member of a class of persons who till the soil as small landowners or as agricultural labourers. The term peasant originally

referred to small-scale agriculturalists in Europe in historic times, but many other societies, both past and present, have had a peasant class.

The peasant economy generally has a relatively simple technology and a division of labour by age and sex. The basic unit of production is the family or

household. One distinguishing characteristic of peasant agriculture is self-sufficiency. Peasant families consume a substantial part of what they produce,

and while some of their output may be sold in the market, their total production is generally not much larger than what is needed for the maintenance of the

family. Both productivity per worker and yields per unit of land are low.

Peasants as a class have tended to disappear as a society industrializes. This is due to the mechanization of farming, the resulting consolidation of

farming plots into larger units, and the accompanying emigration of rural dwellers to the cities and other sites of industrial employment. The small-scale

agriculture associated with peasant labour is simply too inefficient to be economically viable in developed countries.

Source: "peasant." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

Note: The "Peasant class" has not disappeared, it has only been pushed into the brightly lit corridors of prevailing

bureaucracies with walls of political portrait mirrors, glazed marble floors and a skylight filled with an "officialized" artificial Sun, Moon and Stars...

that attempt to use historical definitions of the word "peasant" to undermine and circumvent the perception of its continued existence by presenting the word

"peasant" as a name that is only relevant to a given time and place such as the Medieval era and can only be defined in terms of the ideas involving agriculture or village-level,

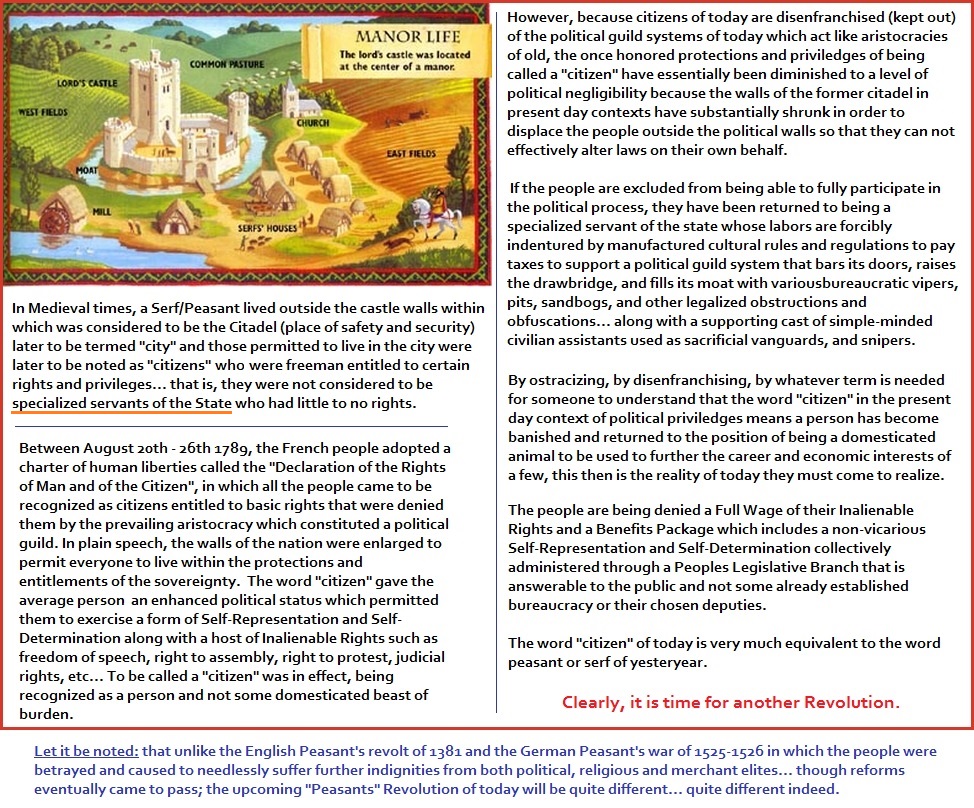

home-based or manor-based enterprises. However, the word "peasant" along with "serf" routinely meant someone who lived outside the citadel (city-grounds) of a

castle and were therefore not viewed as citizens... or denizens of the citadel and were therefore left vulnerable to any marauding groups because they were not

obligingly offered full rights and full protections from those who claimed them as chattel... or domesticated human beasts-of-burden who were forced to toil and

pay annual tribute to those who claimed they were their betters In short, the "peasant class" is alive and well because having such a social class is very

profitable for a few enabled to take advantage of the many. |

Metaphorically speaking, the walls of the present day draw-bridge castles of politics have shrunk so much that the larger population is not provided the same

equal benefits as those "inside" the political guild System. The publics of today have been ostracized, disenfranchised, and other-wise been booted outside

the walls of the current political system which has reduced their "inalienable right" of self-governance to a next-to-nothing negligible privilege.

Time for another Revolution!

(Revolutionists need to develop the appropriate strategy for attacking and taking over the present political castle. You must be able to provide the people

with a viable substitute which addresses the very many inequalities we are being subjected to. You must re-enfranchise the public which symbolically represents

opening up the castle gates, letting down the draw-bridge and expanding the walls to include everyone. This means you will have to adopt a Peoples Legislative

Branch accommodation.) |

No matter what type of castle you survey, all of them used some type of barrier for protection. Yet because the initial grounds behind a wall and/or moat

(water obstruction) were small, the serfs (peasants) were kept outside under the (often illusory) provision that they would be permitted inside whenever danger

arouse from outside, yet there weren't any provisions protecting them from those within the walls who could treat them in any manner they wanted... simply by

making up a law, rule, or practice to establish the perception of "divine right" propriety be it for vice, villainy, or volition based on mental illness that

those in authority all too often try to cover up when "one of their own" exhibits a mental, emotional or physical deficiency (such as the case of Trump who is

obviously unsuited for the position of the Presidency... much less Commander and Chief of the Military... and thus should be subjected to the Uniform Code of

Military Justice and given an Unsuitability discharge. If any other person acted the way he does while being involved with the military, they would have been

subjected to a psychiatric evaluation and provided with a discharge for being unable to carry out their duties without continued and constant assistance

necessitating excuses from political, military and law enforcement leaders... who act like a group of over-paid social workers taking care of high-functioning

mentally-handicapped adult, and represents a culture of deteriorating leaderships exhibiting a double-standard form of duplicitous hypocrisy.)

As populations grew, the walls of the castles expanded to permit more people to live inside the grounds, thus developing the first urban areas while

outside were what we of today might refer to as "out in the sticks, boondocks, boonies, back-country", etc...

The people living inside were eventually referred to as "citizens" with more protections and privileges than peasants, but not full political advantages...

in that they had no power to develop laws. In other words, though they were recognized as "free men", they were still chained to the conventions of a

practiced peasantry that the people of today are experiencing as well. |

|

Upon attempting to research the origin and original meaning (and its later applications to given contexts) of the word "citizen", let me begin by providing

a definition from the Webster's ninth new collegiate dictionary (1986):

Citizen [Middle English citizein, from Anglo-French citezein, alteration of Old French citeien, from cité

city] (14th Century)

- an inhabitant of a city or town especially one entitled to the rights and privileges of a freeman

- —

- a member of a state

- a native or naturalized person who owes allegiance to a government and is entitled to protection from it

- a civilian as distinguished from a specialized servant of the state

|

Etymology:

The supplying of etymologies involves such difficult decisions for a lexicographer as whether words should be carried back into prehistory by means of

reconstructed forms or the degree to which speculation should be permitted. An American Romance scholar, Yakov Malkiel, presented the notion that words follow

"trajectories"—by finding certain points in the history of a word, one can link up the developments in form and meaning. The austere treatment of some

words consists in saying "derivation unknown," and yet this sometimes causes interesting possibilities to be ignored.

A fundamental distinction is made in word history between the "native stock" and the "loanwords." There have been so many borrowings into English that the

language has been called "hypertrophied." The traditional view is to regard the borrowings as a source of "richness." A historical dictionary does its best to

ascertain the date at which a word was adopted from another language, but the word may have to go through a period of probation. Murray, the editor of the OED,

listed four stages of word "citizenship": the casual, the alien, the denizen, and the natural. The casuals may not be part of the language, as they appear only

in travel writings and accounts of foreign countries, but a lexicographer must collect citations for them in order to record the early history of a word that

may later become naturalized. Some words may remain denizens for centuries, Murray pointed out, such as phenomenon treated as Greek, genus as Latin, and

aide-de-camp as French. When a word is borrowed, its etymology may be traced through its descent in its original language.

Some early philosophies assumed that there is a mystic relation between the present use of a word and its origin and that etymology is a search for the

"true meaning." The recognition of continuous linguistic change establishes, however, that etymology is no more than early history, sometimes as reconstructed

on the basis of relationships and known sound changes. Ingenuity in etymologizing is dangerous, and even plausibility can be misleading, but ascertained fact

has overriding importance. It is curious that contemporary slang is often more uncertain in its origin than words of long history. |