page 48

Note: the contents of this page as well as those which precede and follow, must be read as a continuation and/or overlap in order that the continuity about a relationship to/with the dichotomous arrangement of the idea that one could possibly talk seriously about peace from a different perspective as well as the typical dichotomous assignment of Artificial Intelligence (such as the usage of zeros and ones used in computer programming) ... will not be lost (such as war being frequently used to describe an absence of peace and vice-versa). However, if your mind is prone to being distracted by timed or untimed commercialization (such as that seen in various types of American-based television, radio, news media and magazine publishing... not to mention the average classroom which carries over into the everyday workplace), you may be unable to sustain prolonged exposures to divergent ideas about a singular topic without becoming confused, unless the information is provided in a very simplistic manner.

Let's face it, humanity has a lousy definition, accompanying practice, and analysis of peace.

Is peace the opposite of war? Do we automatically have one if the other is not present? Is there a definable transition state between the two which is neither peace nor war? Did either exist before the other was present? Is peace better after (or before) war, and vice versa?

Explained as an expression of parity, we must first decide whether the peace/war idea is an actual construct or something created as a result of a human environment in which the concept of polar opposites is commonplace, and may thus represent a recurring psychological state, but not necessarily a reality except that which we care to define with such terms in order to validate the existence of the idea of dichotomization. However, in terms of physics, let us take a look at the idea of parity:

(Parity) in physics, (is the) property important in the quantum-mechanical description of a physical system. In most cases it relates to the symmetry of the wave function representing a system of fundamental particles. A parity transformation replaces such a system with a type of mirror image. Stated mathematically, the spatial coordinates describing the system are inverted through the point at the origin; that is, the coordinates x, y, and z are replaced with -x, -y, and -z. In general, if a system is identical to the original system after a parity transformation, the system is said to have even parity. If the final formulation is the negative of the original, its parity is odd. For either parity the physical observables, which depend on the square of the wave function, are unchanged. A complex system has an overall parity that is the product of the parities of its components. Until 1956 it was assumed that, when an isolated system of fundamental particles interacts, the overall parity remains the same or is conserved. This conservation of parity implied that, for fundamental physical interactions, it is impossible to distinguish right from left and clockwise from counterclockwise. The laws of physics, it was thought, are indifferent to mirror reflection and could never predict a change in parity of a system. This law of the conservation of parity was explicitly formulated in the early 1930s by the Hungarian-born physicist Eugene P. Wigner and became an intrinsic part of quantum mechanics. In attempting to understand some puzzles in the decay of subatomic particles called K-mesons, the Chinese-born physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang proposed in 1956 that parity is not always conserved. For subatomic particles three fundamental interactions are important: the electromagnetic, strong, and weak forces. Lee and Yang showed that there was no evidence that parity conservation applies to the weak force. The fundamental laws governing the weak force should not be indifferent to mirror reflection, and, therefore, particle interactions that occur by means of the weak force should show some measure of built-in right- or left-handedness that might be experimentally detectable. In 1957 a team led by the Chinese-born physicist Chien-Shiung Wu announced conclusive experimental proof that the electrons ejected along with antineutrinos from certain unstable cobalt nuclei in the process of beta decay, a weak interaction, are predominantly left-handed—that is to say, the spin rotation of the electrons is that of a left-handed screw. Nevertheless, it is believed on strong theoretical grounds (i.e., the CPT theorem) that when the operation of parity reversal P is joined with two others, called charge conjugation C and time reversal T, the combined operation does leave the fundamental laws unchanged. Source: "Parity." (particle physics) Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

Is peace and/or war an actual physical system, or merely a defined psychological state of a given set of physical variables that might be more adequately understood if given alternative terms? If both an actual peace and war are absent, is there not left but a state of limbo? Then again, what if we prefer to use the definition of parity found in economics?

In economics, (parity can be defined as the) equality in price, rate of exchange, purchasing power, or wages. In international exchange, parity refers to the exchange rate between the currencies of two countries making the purchasing power of both currencies substantially equal. Theoretically, exchange rates of currencies can be set at a parity or par level and adjusted to maintain parity as economic conditions change. The adjustments can be made in the marketplace, by price changes, as conditions of supply and demand change. These kinds of adjustment occur naturally if the exchange rates are allowed to fluctuate freely or within wide ranges. If, however, the exchange rates are stabilized or set arbitrarily (as by the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944) or are set within a narrow range, the par rates can be maintained by intervention of national governments or international agencies (e.g., the International Monetary Fund). In U.S. agricultural economics, the term parity was applied to a system of regulating the prices of farm commodities, usually by government price supports and production quotas, in order to provide farmers with the same purchasing power that they had in a selected base period. For example, if the average price received per bushel of wheat during the base period was 98 cents, and, if the prices paid by farmers for other goods quadrupled, then the parity price for wheat would be $3.92 per bushel. Source: "Parity." (economics) Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

If parity is to be defined by the notion of equality or fairness, then this value may thus be used as the defining criteria of right and wrong... in that this type of parity must be achieved at all costs. If rules indicate that one or another "side" of the parity coin appears to be more recurring, artificial steps might be taken to increase the likely-hood of achieving parity... or equality in terms of preventing an uneven occurrence to take place. An example of this might be construed from the history of golf:

Golf International competition The first organized series of regular international matches were between Great Britain and the United States. The amateur team match between the two countries for the Walker Cup was inaugurated in 1922, and the professional team match for the Ryder Cup in 1927. The women's amateur team match for the Curtis Cup began in 1932. Although the competition in all these contests has often been close, the U.S. teams managed to win the cups with great consistency. In an attempt to bring parity to the Ryder Cup, the format was changed in 1979 to broaden the British team to include continental European players as well. This strategy has proved successful, and subsequent Ryder Cup matches have been fiercely contended, with both teams exhibiting excellent play. Between 1979 and 2000 the United States won six times and Europe four times, while one match (1989) ended in a tie. Source: "Golf." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

From the wordweb dictionary we have the following ensemble of definitions to parity:

- Functional equality.

- (obstetrics) the number of liveborn children a woman has delivered. ["the parity of the mother must be considered"]

- (mathematics) a relation between a pair of integers: if both integers are odd or both are even they have the same parity; if one is odd and the

other is even they have different parity. ["parity is often used to check the integrity of transmitted data"]

- (computing) a bit that is used in an error detection procedure in which a 0 or 1 is added to each group of bits so that it will have either an

odd number of 1's or an even number of 1's; e.g., if the parity is odd then any group of bits that arrives with an even number of 1's must contain an

error.

- (physics) parity is conserved in a universe in which the laws of physics are the same in a right-handed system of coordinates as in a left-handed system.

And here is a short list of synonyms:

- check bit

- conservation parity

- para

- para bit

- space-reflection parity

Yet, we still have not established whether peace and war are appropriately defined as parity. Are they equal and must "take turns" allowing one another to surface... though the aggressions of war make it a greedy entity that doesn't like to share the stage or marquee billing? Can they exist without the other, or are they tied to one another like mirror images... or a shadow to an object? Are the labels which we use part of a tradition whose antiquity had those whose perceptions which were faulty, and we of the present do not take time to produce more accurate labels based on a heightened familiarity with a greater level of truth? For example, we of today use many ancient references as described by the names of constellations. Indeed, names such as "Sun", "Earth", and "Stars" are born in an antiquity with a given perception that persists into the present... despite examinations from different perspectives involving a purported "science". And contrary to the Shakespearian adage that a rose by any name would smell as sweet, we can not at all be certain that such a view would hold if human physiology changed or roses became extinct. If the physiology of the human species incrementally changes over time, yet humans retain old words and their accompanying references or use new words to refer to the same old ideas... traditional perspectives may well remain and bog down progress of perception for the whole of society. If the terms peace and war are old labels referencing old ideas that no longer occur on the scale or frequency to produce an environment in which such words were generated, what then do we of the present actually experience if the words peace and war do not adequately fit?

Are peace and war much like the word "atom" that originally meant indivisible but many of us today know that atoms can be divided and that the word and associated ideas were conceptually very elementary? If peace and war are metaphors, are allusions to that indistinctly seen, why can't we see more clearly... or why are the old words and ideas retained, unless they serve the ulterior motivations of those whose positions enable them to influence others to view life's circumstances in a given way. Despite all the research related to cognitive science, humanity may yet be too stupid to generate better ideas or incorporate more useful ideas which supersede the old ideas of peace and war.

When speaking of cognition and focus on scientific thinking, one may think of the book entitled "The cognitive basis of science" (©2005). Its collection of essays from different thinkers on the subject of thinking about the development of "scientific thinking" can be interpreted as forming a basic and authoritative threshold into this area of research... or be viewed as the guesstimated scrawls of different of would-be philosophical doodlers... regardless of how interesting the idea about scientific thinking can be approached from different orientations. Similarly, if one thinks of Einstein as a representative model of the quintessential genius, such a view can be a barrier to questioning his ideas and forming alternative perceptions and opinions. In taking one example from the book, such as the first chapter by Steven Mithen entitled "Human Evolution and the Cognitive Basis of Science", it is not the thesis which one may find themselves at odds with, but that the duration of time and specificities of environmental influence are wholly absent from consideration. Placed into the present context of discussion, if we view peace and war as constructs of scientific thinking, we must note that they exhibit a very primitive form of ideation... in that the issues have not been resolved, but are retained over long expanses of time without any development away from the pendulum taking place between war and peace.

Granted that the chapter was especially written for the context of the book's stated focus, environmental pressures preceding the development of humanity should be taken stock of since the formula produced the conditions for both humanity and humanity's thinking in terms of what is being described as scientific cognition. The essay does not go back nor forward in time enough, nor cover the multi-variant forms of life which have and do exist. By constraining the focus of inquiry to the developmental facets of scientific thinking, this then becomes similar to a type of stone knapping or other specific enterprise from which arise those who are more skilled in the activity and create an institutionalism about scientific thinking... yet none of the researchers may have any actual skills beyond this venue. In other words, attempting to study one or a few aspects of scientific thinking within the confines of a academic setting are quite different from participating in a construction or electrical/mechanical trade. To such an extent, one must wonder how adept such researchers are outside academic settings... and therefore exhibit a constrained appreciation of the scientific process in terms of problem solving which requires an actual hands-on application of trial and error... if such a methods suits the thinking of a given individual, like that described by Edison when he said something to the effect that his ideas were generated by 97% perspiration and 3% inspiration... meaning there was a lot of trial an error involved in his style of "scientific" experimentation.

|

He (Thomas Edison) had the assistance of 26-year-old Francis Upton, a graduate of Princeton University with an M.A. in science. Upton, who joined the laboratory force (of Edison Electric Light Company) in December 1878, provided the mathematical and theoretical expertise that Edison himself lacked. (Edison later revealed, "At the time I experimented on the incandescent lamp I did not understand Ohm's law." On another occasion he said, "I do not depend on figures at all. I try an experiment and reason out the result, somehow, by methods which I could not explain.") One of the accidental discoveries made in the Menlo Park laboratory during the development of the incandescent light anticipated the British physicist J.J. Thomson's discovery of the electron 15 years later. In 1881–82 William J. Hammer, a young engineer in charge of testing the light globes, noted a blue glow around the positive pole in a vacuum bulb and a blackening of the wire and the bulb at the negative pole. This phenomenon was first called "Hammer's phantom shadow," but when Edison patented the bulb in 1883 it became known as the "Edison effect." Scientists later determined that this effect was explained by the thermionic emission of electrons from the hot to the cold electrode, and it became the basis of the electron tube and laid the foundation for the electronics industry. The thrust of Edison's work may be seen in the clustering of his patents: 389 for electric light and power, 195 for the phonograph, 150 for the telegraph, 141 for storage batteries, and 34 for the telephone. His life and achievements epitomize the ideal of applied research. He always invented for necessity, with the object of devising something new that he could manufacture. The basic principles he discovered were derived from practical experiments, invariably by chance, thus reversing the orthodox concept of pure research leading to applied research. Edison's role as a machine shop operator and small manufacturer was crucial to his success as an inventor. Unlike other scientists and inventors of the time, who had limited means and lacked a support organization, Edison ran an inventive establishment. He was the antithesis of the lone inventive genius, although his deafness enforced on him an isolation conducive to conception. His lack of managerial ability was, in an odd way, also a stimulant. As his own boss, he plunged ahead on projects more prudent men would have shunned, then tended to dissipate the fruits of his inventiveness, so that he was both free and forced to develop new ideas. Few men have matched him in the positiveness of his thinking. Edison never questioned whether something might be done, only how. Source: "Edison, Thomas Alva." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

As a "scientific thinker", Edison was a person of his age. If he had been born later or earlier, we might never have heard of him. His skills might not have developed into a useful productivity if he had been born to a group of Neanderthals or even ancient Egyptians. Indeed, there is no telling how many people who have a similar personality but never walk away from a production job, or sitting on a tractor, or turn away from some criminal activity. Given another set of circumstances... the Edison, Einstein or Da Vinci we know, may not have been able to apply their abilities in contexts more crude or sophisticated. Similarly, there is no telling how many creative thinkers have died in senseless wars... even if some people acquire creative insight due to experiences with conflicts.

In taking stock of the history of humanity in terms of what may have influenced the generation of a given culture for a given type of hominine, hominid or human, as a precursor for generating a type of scientific thinking that supersedes everyday conventional forms and practices, the effects of the environment on early forms of human-like species must be taken into account... and likewise be catalogued as that which will no doubt play a part on the future humanity's interpretation, definition and application of themes labeled peace and war. For example, while we align the body build of Neanderthals and others to specific environmental niche's, our assessments do not take into consideration the effects produced by the changing rate of the Earth's rotation from the distant past some 3 to 4 or 5 billion years ago during the "primordial soup, broth or stem" era, and the span of time in which humanity may inhabit, if it is to last the same amount of time since its early inception a few million years ago. As such, we must ask if peace and war are species of phenomena not confined to humanity... and exist only as a symbiotic organism(s)? Do other life forms experience their own variation of peace and war? Does peace and war predate humanity or even all primates? Are they bacteria or viruses that have (or have not) evolved? [Symbiosis definition from the Britannica: "Any association between two species populations that live together is symbiotic, whether the species benefit, harm, or have no effect on one another."]

While a case can be made for peace and war being both good and bad, are they at all necessary, or merely participate in life because conditions make them persist? Are they viruses or cancers? Does human culture precipitate them, or are they always present and become "inflamed" under given circumstances? Upon examination, typical dictionary definitions are wholly inadequate for both peace and war, unless one is inclined to perceive the world from a perspective of conservativism that does not provide for an allowance to think alternatively. If we view peace and war as labels of differentiated cells, we might also want to view them as undifferentiated stem cells that become differentiated by our labeling system into peace or war. For example, a given conflict may be labeled a war by one person and yet another person call it a heated discussion that momentarily got out of hand. Likewise, one person might label the absence of war as a circumstance of peace while another defined it as a state of limbo... neither war nor peace. If peace and war are stem cells that can grow into an either bad or good situation, identifying the stimulus which initiates the development (or cessation).

Clearly, war and peace undergo change or a "renewal" process like those of the epidermis... and may thus exhibit "layers" such as the three layers of skin which correspond to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree burns. If we surmise that the absence of war or peace is due to some unrecognized inhibitory process (or event), it is of value to recognize what it is as much as what controls its effects. In other words, although we say that a war stops by having captured the leaders of another army, why are some conflicts more protracted than others even under conditions of armament privation? Why don't either peace or war persist, if there are not limiting factors? Can we create conditions to make them persist indefinitely? Does war stop because it is merely a case of reduced resources (including "attitude" as a resource)? Are seemingly obvious reasons (such as that which evokes an expression of surrender), the actual state of being... or are the assumptions of peace and war (in whatever era they are defined), merely way-stations or go-betweens something else? Whereas we have taken to claim certain conditions as representations of peace and/or war, are they manufactured substitutes for some underlying process and/or condition which have developed them as expedient expressions... like a naive or crude sign language?

Though we say one set of conditions represent peace and another set of conditions represent war, have peace and war merely become acceptable labels for conventionalized reflexes born in a distant past which enabled them to become habituated... and once habituated, their continuance is manifest like the craving for a narcotic or non-narcotic variant such as religions, sport, business activity, music, food, beverage and holiday traditions? Can humanity break the cycle of habituation and unravel this code of dichotomy? Will humanity have to experience a protracted "cold turkey" period of withdrawal? As it now stands, it appears that humanity "falls off the wagon" and resorts to experiencing the various "highs" associated with war, that may or may not be followed by the "high" (euphoria) of a presumed peace... often followed by an economic recession or depression as part of a cycle of withdrawal due to variable rates of consuming/experiencing an intoxicant, of which there are various kinds in all subject areas. In other words, the cycle of peace and war resemble a cycle of addiction followed by a "drying out" period followed by yet another sequence of the same... again and again and again.

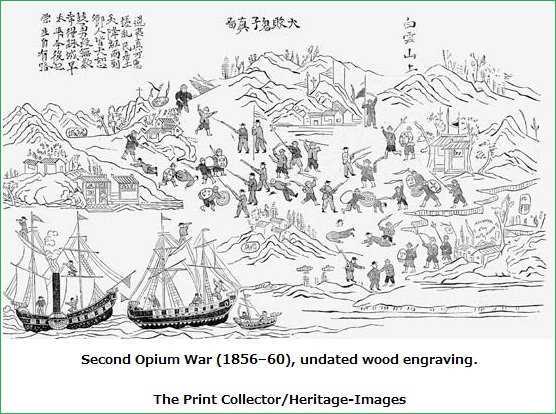

And it should be noted that "respectable" venues of society can exist as an obliging network of substance manufacturers, users, transporters, sales personnel and experimenters... when the word "substance" is removed from its narrow definition along with how substance users and abusers are defined, and can include both peace and war as major or subsidiary substances that can be used and abused because of all the money and power of manipulation to be gained (which caused the 19th century Opium wars due to the United Kingdom's insistence of being able to sell opium though the Chinese were against it). Let's take a look at some commentary about addiction as we close out this essay and move on to the next. Please remember that the following is being related to peace and war when looked upon as substances which can create habituations and increased levels of tolerance, as well as being easily overlooked as substances which can be abused because an entire community or nation can unknowingly participate in the cover-up of such a condition because of the complexity of social interactions which can be tied into the activities of peace and war so that they become acceptable social institutions because their rationalizations legitimize numerous activities of the various people associated thereto. People can become addicted to god or some religious passage or killing, or making money by way of military activity. Indeed, even religious charity has become a money-making and social status vehicle so much so no one is looking for a means to make the need for charity obsolete.

Drug Use The functions of psychotropic drugs To consider drugs only as medicinal agents or to insist that drugs be confined to prescribed medical practice is to fail to understand human nature. The remarks of the American sociologist Bernard Barber are poignant in this regard: Not only can nearly anything be called a "drug," but things so called turn out to have an enormous variety of psychological and social functions—not only religious and therapeutic and "addictive," but political and aesthetic and ideological and aphrodisiac and so on. Indeed, this has been the case since the beginning of human society. It seems that always and everywhere drugs have been involved in just about every psychological and social function there is, just as they are involved in every physiological function. Popular misconceptions Common misconceptions concerning drug addiction have traditionally caused bewilderment whenever serious attempts were made to differentiate states of addiction or degrees of abuse. For many years, a popular misconception was the stereotype that a drug user is a socially unacceptable criminal. The carryover of this conception from decades past is easy to understand but not very easy to accept today. A second misconception involves the ways in which drugs are defined. Many substances are capable of acting on a biological system, and whether a particular substance comes to be considered a drug of abuse depends in large measure upon whether it is capable of eliciting a "druglike" effect that is valued by the user. Hence, a substance's attribute as a drug is imparted to it by use. Caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol are clearly drugs, and the habitual, excessive use of coffee, tobacco, or an alcoholic drink is clearly drug dependence if not addiction. The same could be extended to cover tea, chocolates, or powdered sugar, if society wished to use and consider them that way. The task of defining addiction, then, is the task of being able to distinguish between opium and powdered sugar while at the same time being able to embrace the fact that both can be subject to abuse. This requires a frame of reference that recognizes that almost any substance can be considered a drug, that almost any drug is capable of abuse, that one kind of abuse may differ appreciably from another kind of abuse, and that the effect valued by the user will differ from one individual to the next for a particular drug, or from one drug to the next drug for a particular individual. This kind of reference would still leave unanswered various questions of availability, public sanction, and other considerations that lead people to value and abuse one kind of effect rather than another at a particular moment in history, but it does at least acknowledge that drug addiction is not a unitary condition. Physiological effects of addiction Certain physiological effects are so closely associated with the heavy use of opium and its derivatives that they have come to be considered characteristic of addictions in general. Some understanding of these physiological effects is necessary in order to appreciate the difficulties that are encountered in trying to include all drugs under a single definition that takes as its model opium. Tolerance is a physiological phenomenon that requires the individual to use more and more of the drug in repeated efforts to achieve the same effect. At a cellular level this is characterized by a diminishing response to a foreign substance (drug) as a result of adaptation. Although opiates are the prototype, a wide variety of drugs elicit the phenomenon of tolerance, and drugs vary greatly in their ability to develop tolerance. Opium derivatives rapidly produce a high level of tolerance; alcohol and the barbiturates a very low level of tolerance. Tolerance is characteristic for morphine and heroin and, consequently, is considered a cardinal characteristic of narcotic addiction. In the first stage of tolerance, the duration of the effects shrinks, requiring the individual to take the drug either more often or in greater amounts to achieve the effect desired. This stage is soon followed by a loss of effects, both desired and undesired. Each new level quickly reduces effects until the individual arrives at a very high level of drug with a correspondingly high level of tolerance. Humans can become almost completely tolerant to 5,000 milligrams of morphine per day, even though a "normal" clinically effective dosage for the relief of pain would fall in the range of 5 to 20 milligrams. An addict can achieve a daily level that is nearly 200 times the dose that would be dangerous for a normal pain-free adult. Tolerance for a drug may be completely independent of the drug's ability to produce physical dependence. There is no wholly acceptable explanation for physical dependence. It is thought to be associated with central-nervous-system depressants, although the distinction between depressants and stimulants is not as clear as it was once thought to be. Physical dependence manifests itself by the signs and symptoms of abstinence when the drug is withdrawn. All levels of the central nervous system appear to be involved, but a classic feature of physical dependence is the "abstinence" or "withdrawal" syndrome. If the addict is abruptly deprived of a drug upon which the body has physical dependence, there will ensue a set of reactions, the intensity of which will depend on the amount and length of time that the drug has been used. If the addiction is to morphine or heroin, the reaction will begin within a few hours of the last dose and will reach its peak in one to two days. Initially there is yawning, tears, a running nose, and perspiration. The addict lapses into a restless, fitful sleep and, upon awakening, experiences a contraction of pupils, gooseflesh, hot and cold flashes, severe leg pains, generalized body aches, and constant movement. The addict then experiences severe insomnia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. At this time the individual has a fever, mild high blood pressure, loss of appetite, dehydration, and a considerable loss of body weight. These symptoms continue through the third day and then decline over the period of the next week. There are variations in the withdrawal reaction for other drugs; in the case of the barbiturates, minor tranquilizers, and alcohol, withdrawal may be more dangerous and severe. During withdrawal, drug tolerance is lost rapidly. The withdrawal syndrome may be terminated at any time by an appropriate dose of the addicting drug. Addiction, habituation, and dependence The traditional distinction between “addiction” and “habituation” centres on the ability of a drug to produce tolerance and physical dependence. the opiates clearly possess the potential to massively challenge the body's resources, and, if so challenged, the body will make the corresponding biochemical, physiological, and psychological readjustment to the stress. At this point, the cellular response has so altered itself as to require the continued presence of the drug to maintain normal function. When the substance is abruptly withdrawn or blocked, the cellular response becomes abnormal for a time until a new readjustment is made. The key to this kind of conception is the massive challenge that requires radical adaptation. Some drugs challenge easily, but it is not so much whether a drug can challenge easily as it is whether the drug was actually taken in such a way as to present the challenge. Drugs such as caffeine, nicotine, bromide, the salicylates, cocaine, amphetamine and other stimulants, and certain tranquilizers and sedatives are normally not taken in sufficient amounts to present the challenge. They typically but not necessarily induce a strong need or craving emotionally or psychologically without producing the physical dependence that is associated with “hard” addiction. Consequently, their propensity for potential danger is judged to be less, so that continued use would lead one to expect habituation but not addiction. The key word here is expect. These drugs, in fact, are used excessively on occasion and, when so used, do produce tolerance and withdrawal signs. Morphine, heroin, other synthetic opiates, and to a lesser extent codeine, alcohol, and the barbiturates, all carry a high propensity for potential danger in that all are easily capable of presenting a bodily challenge. Consequently, they are judged to be addicting under continued use. The ultimate effect of a particular drug, in any event, depends as much or more on the setting, the expectation of the user, the user's personality, and the social forces that play upon the user as it does on the pharmacological properties of the drug itself. Enormous difficulties were encountered in trying to apply these definitions of addiction and habituation because of the wide variations in the pattern of use. (The one common denominator in drug use is variability.) As a result, in 1964 the World Health Organization recommended a new standard that replaces both the term drug addiction and the term drug habituation with the term drug dependence, which in subsequent decades became more and more commonplace in describing the need to use a substance to function or survive. Drug dependence is defined as a state arising from the repeated administration of a drug on a periodic or continual basis. Its characteristics will vary with the agent involved, and this must be made clear by designating drug dependence as being of a particular type—that is, drug dependence of morphine type, of cannabis type, of barbiturate type, and so forth. As an example, drug dependence of a cannabis (marijuana) type is described as a state involving repeated administration, either periodic or continual. Its characteristics include (1) a desire or need for repetition of the drug for its subjective effects and the feeling of enhancement of one's capabilities that it effects, (2) little or no tendency to increase the dose since there is little or no tolerance development, (3) a psychological dependence on the effects of the drug related to subjective and individual appreciation of those effects, and (4) absence of physical dependence so that there is no definite and characteristic abstinence syndrome when the drug is discontinued. Considerations of tolerance and physical dependence are not prominent in this definition, although they are still conspicuously present. Instead, the emphasis tends to be shifted in the direction of the psychological or psychiatric makeup of the individual and the pattern of use of the individual and his or her subculture. Several considerations are involved here. There is the concept of psychological reliance in terms of both a sense of well-being and a permanent or semipermanent pattern of behaviour. There is also the concept of gratification by chemical means that has been substituted for other means of gratification. In brief, the drug has been substituted for adaptive behaviour. Descriptions such as hunger, need, craving, emotional dependence, habituation, or psychological dependence tend to connote a reliance on a drug as a substitute gratification in the place of adaptive behaviour. Psychological dependence Several explanations have been advanced to account for the psychological dependence on drugs, but as there is no one entity called addiction, so there is no one picture of the drug user. The great majority of addicts display “defects” in personality. Several legitimate motives of humans can be fulfilled by the use of drugs. There is the relief of anxiety, the seeking of elation, the avoidance of depression, and the relief of pain. For these purposes, the several potent drugs are equivalent, but they do differ in the complications that ensue. Should the user develop physical dependence, euphoric effects become difficult to attain, and the continued use of the drug is apt to be aimed primarily at preventing withdrawal symptoms. It has been suggested that drug use can represent a primitive search for euphoria, an expression of prohibited infantile cravings, or the release of hostility and of contempt; the measure of self-destruction that follows can constitute punishment and the act of expiation. This type of psychodynamic explanation assumes that the individual is predisposed to this type of psychological adjustment prior to any actual experience with drugs. It has also been suggested that the type of drug used will be strongly influenced by the individual's characteristic way of relating to the world. The detached type of person might be expected to choose the “hard” narcotics to facilitate indifference and withdrawal from the world. Passive and ambivalent types might be expected to select sedatives to assure a serene dependency. Passive types of persons who value independence might be expected to enlarge their world without social involvement through the use of hallucinogenic drugs, whereas the dependent type of person who is geared to activity might seek stimulants. Various types of persons might experiment with drugs simply in order to play along with the group that uses drugs; such group identification may be joined with youthful rebellion against society as a whole. Obviously, the above descriptions are highly speculative because of the paucity of controlled clinical studies. The quest of the addict may be the quest to feel full, sexually satisfied, without aggressive strivings, and free of pain and anxiety. Utopia would be to feel normal, and this is about the best that the narcotic addict can achieve by way of drugs. Although many societies associate addiction with criminality, most countries regard addiction as a medical problem to be dealt with in appropriate therapeutic ways. Furthermore, narcotics fulfill several socially useful functions in those countries that do not prohibit or necessarily censure the possession of narcotics. In addition to relieving mental or physical pain, opiates have been used medicinally in tropical countries where large segments of the population suffer from dysentery and fever. History of drug control The first major national efforts to control the distribution of narcotic and other dangerous drugs were the efforts of the Chinese in the 19th century. Commerce in opium poppy and coca leaf (cocaine) developed on an organized basis during the 1700s. The Qing rulers of China attempted to discourage opium importation and use, but the English East India Company, which maintained an official monopoly over British trade in China, was engaged in the profitable export of opium from India to China. This monopoly of the China trade was eventually abolished in 1839–42, and friction increased between the British and the Chinese over the importation of opium. Foreign merchants, including those from France and the United States, were bringing in ever-increasing quantities of opium. Finally, the Qing government required all foreign merchants to surrender their stocks of opium for destruction. The British objected, and the Opium War (1839-42) between the Chinese and the British followed. The Chinese lost and were forced into a series of treaties with England and other countries that took advantage of the British victory. Following renewed hostilities between the British and Chinese, fighting broke out again, resulting in the second Opium War (1856-60). In 1858 the importation of opium into China was legalized by the treaties of Tianjin, which fixed a tariff rate for opium importation. Further difficulties followed. An illegal opium trade carried on by smugglers in southern China encouraged gangsterism and piracy, and the activity eventually became linked with powerful secret societies in the south of China.

Source: "Drug Use." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

Needless to say that the history of drug control is big business for both those in and out of the government. Tens of thousands of people along with billions of dollars are used for addressing various drug issues, though they might not include substances such as caffeine and nicotine as well as peace and war... though they could be, along with religion, Capitalism (used to define greed), alcohol, gambling, slavery, sex trades, etc... And it should not be overlooked that experience gained in one social exercise can well be used in another. Explicitly stated, the presence, duration and effectiveness of controlling war and peace (and thus perhaps predicting them), can be pursued by using techniques of control in other social efforts by government bodies. If conditions of peace provide a given government's administration with what it wants then there can be peace... but if it is war that provides what it wants, then it will be war... no matter how many of one's own people or troops have to be sacrificed in order to outrage the public to support war activity.

Date of Origination: Sunday, 2-April-2017... 05:31 AM

Date of initial posting: Tuesday, 11-April-2017... 2:03 PM Updated posting: Saturday, 31-March-2018... 12:32 PM