page 46

Note: the contents of this page as well as those which precede and follow, must be read as a continuation and/or overlap in order that the continuity about a relationship to/with the dichotomous arrangement of the idea that one could possibly talk seriously about peace from a different perspective as well as the typical dichotomous assignment of Artificial Intelligence (such as the usage of zeros and ones used in computer programming) ... will not be lost (such as war being frequently used to describe an absence of peace and vice-versa). However, if your mind is prone to being distracted by timed or untimed commercialization (such as that seen in various types of American-based television, radio, news media and magazine publishing... not to mention the average classroom which carries over into the everyday workplace), you may be unable to sustain prolonged exposures to divergent ideas about a singular topic without becoming confused, unless the information is provided in a very simplistic manner.

Let's face it, humanity has a lousy definition, accompanying practice, and analysis of peace.

Imagery

(From the Wordweb dictionary:)

- The ability to form mental images of things or events ("he could still hear her in his mental imagery").

- Figurative writing or speaking; vivid descriptions presenting or suggesting images.

If we discuss the topic of peace as an expression of imagery as yet another alternative model in our efforts to assist us in elucidating its recurring absence for extended periods of time... that it is the image of some-thing (though a religious-minded person might want to make a claim that peace is but an image— a symbolic representation of God or some aspect of religious belief); we must then attempt to describe what kind of image it is... or at least what it isn't. However, since the concept of imagery may not be too clear in the mind of some readers, it will prove worthwhile to provide some examples... as we emphasize that we are thinking in terms of peace as that which can be objectified... though the word "imagery" can be applied to different interests. Indeed, many a politician may well view themselves in some sense as an artist, musician, scientist, philosopher, or some other characteristic which they interpret as providing them with a qualitative intellectual advantage over one or more others in their profession... though as is in most cases, they are simply able in a position to take advantage of a given set of social variables that others might well overlook or deliberately discard because they are questionable to their definition of morality, truth, justice, equality, patriotism, or whatever comes to mind as a divining rod.

And though some would prefer to view the term "imagery" in the sense of conveying a fairy tale or myth, we will nonetheless proceed on the footing that "peace" is a type of imagery and it is something which exists and can be personified objectively... if only in an imaginative context for those whose minds are enabled to craftily create the contextual setting like a stage scene. The reader is encouraged to "read into" the following excerpt on Sculpture taken from the Britannica. Whereas the word "sculpture" is being spoken of, one has to think in terms of the "peace" topic as a word and idea to be substituted. Nonetheless, having a malleable imagination is a requirement for discussing the topic of imagery... whether in anthropology, architecture, art, biology, math, medicine, music, physics, poetry, religion, sociology, or some other science, sport or doodling past-time.

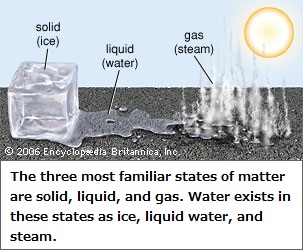

In other words, you don't have to be too literal in your perceptions such that by simply substituting the word "peace" for "sculpture" and expecting all the words being used in the context of sculpture to automatically ensure a direct cross-reference. One's mind must be able to move freely between the states of fluidity, wistfulnesss, and solidity... like the three conventionally known states of matter (liquid, gas, solid) by way of an internal catalyst of creative thinking. As such, the topic of Peace can be viewed multi-dimensionally... like a piece of stone, block of wood or ice... whose internal image is brought forth when all its rough edges are chipped (hewn) away. Such is the state of peace... in a raw state of being that is worshipped as it is and only amateur researchers on the topic of peace have attempted to let its true nature and essence be seen in full daylight from all vantage points of perception. Peace, like sculpture can no longer be confined to the dimension of being defined as a visual art, or just three dimensions... since a song or piece of music can be defined as an aural sculpture and the other senses (with or without some artificialized extension such as a hearing aid, glasses, or other electronic perception, etc...). Indeed, the wisemen of the "wisemen and the elephant" poem fame would take exception to the claim that sculpture is best defined by the visual arts alone. (See the bottom of: Let's talk peace page 27.)

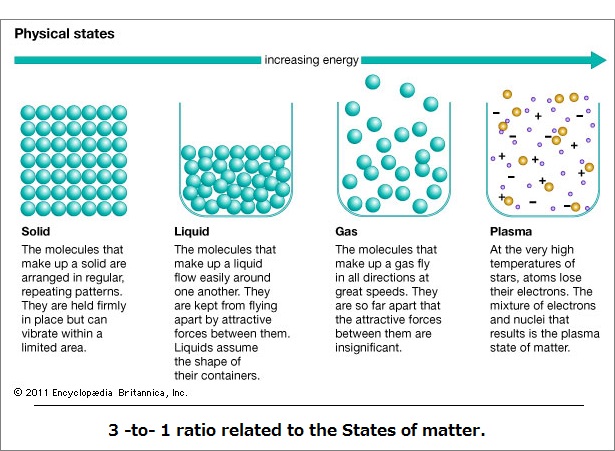

While the 3 (liquid, gas, solid) states of matter are widely known, the plasma state is not conventionally thought of, nor is the "state" of matter -to- energy conversion. As such, the 3 states of matter is a convention of thought which can traditionalize mental dimensionality into a convention that binds one's perceptual orientations. As such, let us digress for a moment and pictorially review alternatives to the typical convention, though they too... in their own arena of application, represent other conventions of consideration, so that one might think in terms of energy conversions and comparative contents (of proportionality) that can be aligned to the topics of sculpture and peace... since art, like science, both have their own inherent energy, sport, and biology as well as strategy we humans only think we are cognitively privy to... that is, metaphorically applied:

|

|

|

|

As an application of creative thinking in the following introduction, the list of media needs to be expanded to include emotional (gaseous) and intellectual (fluidic) considerations to go along with the different solidifications of glass, wood, metal, etc. In such an instance we can refer to such an idea as having a dream within a dream within a dream (like a series of nested Russian dolls); can be used as an abstract simplification of such an idea because they represent a 3 in 1 characteristic that appear similar but have distinct "embodying" characteristics. Yet for those who have not experienced a dream within a dream, much less a triadic assortment thereof, the comparison may be too far-fetched for them to even approximate an understanding. For example, while history does not record Dante ever claiming to have experienced a dream within a dream within a dream, some of us have suspected he did when he wrote about The Divine Comedy, with its Heaven, Purgatory and Hell... which was written in the language of the common people and not the upper class (Latin) of his time, and has since become the dominant formula of speech... as well as having encapsulated a type of associated thinking process which has gone unnoticed by many historians and readers of The Divine Comedy— who unknowingly involve themselves with the three levels (Heaven, Purgatory, Hell), the three languages ("vulgar" Italian, Religion, Latin), and the three characters of the story (Virgil, Beatrice, Dante)... which is a grouping of three within three amongst three socio-economic groups... and some think that the recurring themes of "three" in his writing is explained by a religious "Trinity" influence instead of looking at it as an underlying cognitive pattern to be found in other-than religious contexts as well. The trouble is that most historians do not supply cross- references from other subject areas and are not aware of numerically referenced cognitive patterns occurring in an incrementally deteriorating environment.

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieriborn c. May 21- June 20, 1265, Florence, Italy died Sept. 13/14, 1321, Ravenna Italian poet, prose writer, literary theorist, moral philosopher, and political thinker. He is best known for the monumental epic poem La commedia, later named La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy). Dante's Divine Comedy, a great work of medieval literature, is a profound Christian vision of man's temporal and eternal destiny. On its most personal level, it draws on the poet's own experience of exile from his native city of Florence; on its most comprehensive level, it may be read as an allegory, taking the form of a journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise. The poem amazes by its array of learning, its penetrating and comprehensive analysis of contemporary problems, and its inventiveness of language and imagery. By choosing to write his poem in Italian rather than in Latin, Dante decisively influenced the course of literary development. Not only did he lend a voice to the emerging lay culture of his own country, but Italian became the literary language in western Europe for several centuries. In addition to poetry Dante wrote important theoretical works ranging from discussions of rhetoric to moral philosophy and political thought. He was fully conversant with the classical tradition, drawing for his own purposes on such writers as Virgil, Cicero, and Boethius. But, most unusual for a layman, he also had an impressive command of the most recent scholastic philosophy and of theology. His learning and his personal involvement in the heated political controversies of his age led him to the composition of De monarchia, one of the major tracts of medieval political philosophy. Source: "Dante." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

However, the present essay is not about adding a new dimension to the idea of Sculpture, but increasing the dimensions of thought associated to the concept(s) of peace in order to better appreciate it as a primivity of expression (definition, application) requiring the adoption of new ideas related to something that has remained unchanged for centuries. In other words, the concept of peace (and of war) have not substantially changed. While the severity of war has been increased as has the superficiality of peace, both have been treated like ancient inviolable relics that the world is forced... by way of tradition... to pay homage to and make periodic pilgrimages to— again, and again, and again. Although pilgrimages are most often related to religious practices, the act of "pilgrimaging" is a behavior that should be looked at like basic cognitive patterns which also exist outside the domain of religion. Hence, recurrences of progress, depression, war, peace, mass insanity, etc., are cyclical patterns of behavior that can be traced to changes in the environment... and are not understood as such because the effects of the changing environment are not well understood. Some patterns occur over distant times and places without being adequately recorded and thus not made available to interested researchers... much less find a receptive audience that would provide additional funding for more extensive research efforts.

|

Sculpture

Introduction (Sculpture is) an artistic form in which hard or plastic materials are worked into three-dimensional art objects. The designs may be embodied in freestanding objects, in reliefs on surfaces, or in environments ranging from tableaux to contexts that envelop the spectator. An enormous variety of media may be used, including clay, wax, stone, metal, fabric, glass, wood, plaster, rubber, and random "found" objects. Materials may be carved, modeled, molded, cast, wrought, welded, sewn, assembled, or otherwise shaped and combined. Sculpture is not a fixed term that applies to a permanently circumscribed category of objects or sets of activities. It is, rather, the name of an art that grows and changes and is continually extending the range of its activities and evolving new kinds of objects. The scope of the term was much wider in the second half of the 20th century than it had been only two or three decades before, and in the fluid state of the visual arts at the turn of the 21st century nobody can predict what its future extensions are likely to be. Certain features which in previous centuries were considered essential to the art of sculpture are not present in a great deal of modern sculpture and can no longer form part of its definition. One of the most important of these is representation. Before the 20th century, sculpture was considered a representational art, one that imitated forms in life, most often human figures but also inanimate objects, such as game, utensils, and books. Since the turn of the 20th century, however, sculpture has also included nonrepresentational forms. It has long been accepted that the forms of such functional three-dimensional objects as furniture, pots, and buildings may be expressive and beautiful without being in any way representational; but it was only in the 20th century that nonfunctional, nonrepresentational, three-dimensional works of art began to be produced. Before the 20th century, sculpture was considered primarily an art of solid form, or mass. It is true that the negative elements of sculpture—the voids and hollows within and between its solid forms—have always been to some extent an integral part of its design, but their role was a secondary one. In a great deal of modern sculpture, however, the focus of attention has shifted, and the spatial aspects have become dominant. Spatial sculpture is now a generally accepted branch of the art of sculpture. It was also taken for granted in the sculpture of the past that its components were of a constant shape and size and, with the exception of items such as Augustus Saint-Gaudens's Diana (a monumental weather vane), did not move. With the recent development of kinetic sculpture, neither the immobility nor immutability of its form can any longer be considered essential to the art of sculpture. Finally, sculpture since the 20th century has not been confined to the two traditional forming processes of carving and modeling or to such traditional natural materials as stone, metal, wood, ivory, bone, and clay. Because present-day sculptors use any materials and methods of manufacture that will serve their purposes, the art of sculpture can no longer be identified with any special materials or techniques. Through all these changes, there is probably only one thing that has remained constant in the art of sculpture, and it is this that emerges as the central and abiding concern of sculptors: the art of sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that is especially concerned with the creation of form in three dimensions. Sculpture may be either in the round or in relief. A sculpture in the round is a separate, detached object in its own right, leading the same kind of independent existence in space as a human body or a chair. A relief does not have this kind of independence. It projects from and is attached to or is an integral part of something else that serves either as a background against which it is set or a matrix from which it emerges. The actual three-dimensionality of sculpture in the round limits its scope in certain respects in comparison with the scope of painting. Sculpture cannot conjure the illusion of space by purely optical means or invest its forms with atmosphere and light as painting can. It does have a kind of reality, a vivid physical presence that is denied to the pictorial arts. The forms of sculpture are tangible as well as visible, and they can appeal strongly and directly to both tactile and visual sensibilities. Even the visually impaired, including those who are congenitally blind, can produce and appreciate certain kinds of sculpture. It was, in fact, argued by the 20th-century art critic Sir Herbert Read that sculpture should be regarded as primarily an art of touch and that the roots of sculptural sensibility can be traced to the pleasure one experiences in fondling things. All three-dimensional forms are perceived as having an expressive character as well as purely geometric properties. They strike the observer as delicate, aggressive, flowing, taut, relaxed, dynamic, soft, and so on. By exploiting the expressive qualities of form, a sculptor is able to create images in which subject matter and expressiveness of form are mutually reinforcing. Such images go beyond the mere presentation of fact and communicate a wide range of subtle and powerful feelings. The aesthetic raw material of sculpture is, so to speak, the whole realm of expressive three-dimensional form. A sculpture may draw upon what already exists in the endless variety of natural and man-made form, or it may be an art of pure invention. It has been used to express a vast range of human emotions and feelings from the most tender and delicate to the most violent and ecstatic. All human beings, intimately involved from birth with the world of three-dimensional form, learn something of its structural and expressive properties and develop emotional responses to them. This combination of understanding and sensitive response, often called a sense of form, can be cultivated and refined. It is to this sense of form that the art of sculpture primarily appeals. Forms, subject matter, imagery, and symbolism of sculpture A great deal of sculpture is designed to be placed in public squares, gardens, parks, and similar open places or in interior positions where it is isolated in space and can be viewed from all directions. Other sculpture is carved in relief and is viewed only from the front and sides. Sculpture in the round

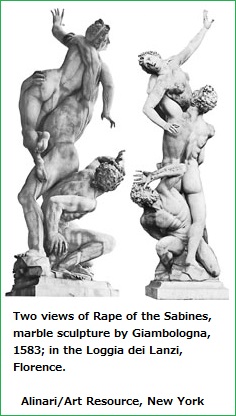

The opportunities for free spatial design that such freestanding sculpture presents are not always fully exploited. The work may be designed, like many Archaic sculptures, to be viewed from only one or two fixed positions, or it may in effect be little more than a four-sided relief that hardly changes the three-dimensional form of the block at all. Sixteenth-century Mannerist sculptors, on the other hand, made a special point of exploiting the all-around visibility of freestanding sculpture. Giambologna's Rape of the Sabines, for example, compels the viewer to walk all around it in order to grasp its spatial design. It has no principal views; its forms move around the central axis of the composition, and their serpentine movement unfolds itself gradually as the spectator moves around to follow them. Much of the sculpture of Henry Moore and other 20th-century sculptors is not concerned with movement of this kind, nor is it designed to be viewed from any fixed positions. Rather, it is a freely designed structure of multidirectional forms that is opened up, pierced, and extended in space in such a way that the viewer is made aware of its all-around design largely by seeing through the sculpture. The majority of constructed sculptures are disposed in space with complete freedom and invite viewing from all directions. In many instances the spectator can actually walk under and through them. The way in which a freestanding sculpture makes contact with the ground or with its base is a matter of considerable importance. A reclining figure, for example, may in effect be a horizontal relief. It may blend with the ground plane and appear to be rooted in the ground like an outcrop of rock. Other sculptures, including some reclining figures, may be designed in such a way that they seem to rest on the ground and to be independent of their base. Others are supported in space above the ground. The most completely freestanding sculptures are those that have no base and may be picked up, turned in the hands, and literally viewed all around like a netsuke (a small toggle of wood, ivory, or metal used to fasten a small pouch or purse to a kimono sash). Of course, a large sculpture cannot actually be picked up in this way, but it can be designed so as to invite the viewer to think of it as a detached, independent object that has no fixed base and is designed all around. Sculpture designed to stand against a wall or similar background or in a niche may be in the round and freestanding in the sense that it is not attached to its background like a relief; but it does not have the spatial independence of completely freestanding sculpture, and it is not designed to be viewed all around. It must be designed so that its formal structure and the nature and meaning of its subject matter can be clearly apprehended from a limited range of frontal views. The forms of the sculpture, therefore, are usually spread out mainly in a lateral direction rather than in depth. Greek pedimental sculpture illustrates this approach superbly: the composition is spread out in a plane perpendicular to the viewer's line of sight and is made completely intelligible from the front. Seventeenth-century Baroque sculptors, especially Bernini, adopted a rather different approach. Though some favoured a coherent frontal viewpoint, however active, Bernini is known to have conceived a work (the Apollo and Daphne) in which the narrative unfolded in details discovered as the viewer walked around the work, beginning from the rear. The frontal composition of wall and niche sculpture does not necessarily imply any lack of three-dimensionality in the forms themselves; it is only the arrangement of the forms that is limited. Classical pedimental sculpture, Indian temple sculpture such as that at Khajuraho, Gothic niche sculpture, and Michelangelo's Medici tomb figures are all designed to be placed against a background, but their forms are conceived with a complete fullness of volume. Relief sculpture Relief sculpture is a complex art form that combines many features of the two-dimensional pictorial arts and the three-dimensional sculptural arts. On the one hand, a relief, like a picture, is dependent on a supporting surface, and its composition must be extended in a plane in order to be visible. On the other hand, its three-dimensional properties are not merely represented pictorially but are in some degree actual, like those of fully developed sculpture. Among the various types of relief are some that approach very closely the condition of the pictorial arts. The reliefs of Donatello, Ghiberti, and other early Renaissance artists make full use of perspective, which is a pictorial method of representing three-dimensional spatial relationships realistically on a two-dimensional surface. Egyptian and most pre-Columbian American low reliefs are also extremely pictorial but in a different way. Using a system of graphic conventions, they translate the three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional one. The relief image is essentially one of plane surfaces and could not possibly exist in three dimensions. Its only sculptural aspects are its slight degree of actual projection from a surface and its frequently subtle surface modeling. Other types of relief—for example, Classical Greek and most Indian—are conceived primarily in sculptural terms. The figures inhabit a space that is defined by the solid forms of the figures themselves and is limited by the background plane. This back plane is treated as a finite, impenetrable barrier in front of which the figures exist. It is not conceived as a receding perspective space or environment within which the figures are placed nor as a flat surface upon which they are placed. The reliefs, so to speak, are more like contracted sculpture than expanded pictures. The central problem of relief sculpture is to contract or condense three-dimensional solid form and spatial relations into a limited depth space. The extent to which the forms actually project varies considerably, and reliefs are classified on this basis as low reliefs (bas-reliefs) or high reliefs. There are types of reliefs that form a continuous series from the almost completely pictorial to the almost fully in the round. One of the relief sculptor's most difficult tasks is to represent the relations between forms in depth within the limited space available to him. He does this mainly by giving careful attention to the planes of the relief. In a carved relief the highest, or front, plane is defined by the surface of the slab of wood or stone in which the relief is carved; and the back plane is the surface from which the forms project. The space between these two planes can be thought of as divided into a series of planes, one behind the other. The relations of forms in depth can then be thought of as relations between forms lying in different planes. Sunken relief is also known as incised, coelanaglyphic, and intaglio relief. It is almost exclusively an ancient Egyptian art form, but some beautiful small-scale Indian examples in ivory have been discovered at Bagra-m in Afghanistan. In a sunken relief, the outline of the design is first incised all around. The relief is then carved inside the incised outline, leaving the surrounding surface untouched. Thus, the finished relief is sunk below the level of the surrounding surface and is contained within a sharp, vertical-walled contour line. This approach to relief sculpture preserves the continuity of the material's original surface and creates no projection from it. The outline shows up as a powerful line of light and shade around the whole design.

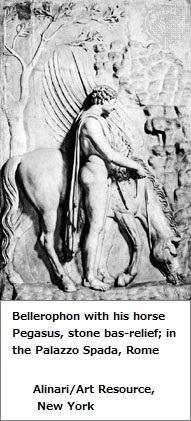

Figurative low relief is generally regarded by sculptors as an extremely difficult art form. To give a convincing impression of three-dimensional structure and surface modeling with only a minimal degree of projection demands a fusion of draftsmanship and carving or modeling skill of a high order. The sculptor has to proceed empirically, constantly changing the direction of his light and testing the optical effect of his work. He cannot follow any fixed rules or represent things in depth by simply scaling down measurements mathematically, so that, say, one inch of relief space represents one foot. The forms of low relief usually make contact with the background all around their contours. If there is a slight amount of undercutting, its purpose is to give emphasis, by means of cast shadow, to a contour rather than to give any impression that the forms are independent of their background. Low relief includes figures that project up to about half their natural circumference. Technically, the simplest kind of low relief is the two-plane relief. For this, the sculptor draws an outline on a surface and then cuts away the surrounding surface, leaving the figure raised as a flat silhouette above the background plane. This procedure is often used for the first stages of a full relief carving, in which case the sculptor will proceed to carve into the raised silhouette, rounding the forms and giving an impression of three-dimensional structure. In a two-plane relief, however, the silhouette is left flat and substantially unaltered except for the addition of surface detail. Pre-Columbian sculptors used this method of relief carving to create bold figurative and abstract reliefs. Stiacciato relief is an extremely subtle type of flat, low relief carving that is especially associated with the 15th-century sculptors Donatello and Desiderio da Settignano. The design is partly drawn with finely engraved chisel lines and partly carved in relief. The stiacciato technique depends largely for its effect on the way in which pale materials, such as white marble, respond to light and show up the most delicate lines and subtle changes of texture or relief. The forms of high relief project far enough to be in some degree independent of their background. As they approach the fullness of sculpture in the round, they become of necessity considerably undercut. In many high reliefs, where parts of the composition are completely detached from their background and fully in the round, it is often impossible to tell from the front whether or not a figure is actually attached to its background. Many different degrees of projection are often combined in one relief composition. Figures in the foreground may be completely detached and fully in the round, while those in the middle distance are in about half relief and those in the background in low relief. Such effects are common in late Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque sculpture. Leonard R. Rogers: Sculptor and writer. Former Head, Faculty of Three-Dimensional Design, College of Art and Design, Loughborough, England. Author of Sculpture: Appreciation of the Arts; Relief Sculpture.Source: "Sculpture." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

Like a piece of sculpture or other so-designated "art form", peace...and/or war as well as the peace/war or war/peace combinations, are themselves readily admissible to such genres. However, if they are kept in this or other artistically expressive realm, they are not themselves looked upon as being problematic and will not be addressed as such with the extent of being attended to with efforts to resolve the issues. Instead, they are looked upon as natural forms of human expression which help to define specific human players and associated participants like those involved in a theatrical production or other artistic show. They become part of a culture or are used to establish a culture of which there are different variants. Instead of being viewed as problems needing answers, they are accepted as a given and permitted to prosper in different climates in different ways; each with their own rationalized justifications. Attempts to break up such cultures would necessarily cause some to cry foul, though it is they who participate in keeping the stench alive and well... like a person who sits so long on a toilet they can no longer recognize their own putrid smell.

Date of Origination: Friday, 30-March-2017... 06:12 AM

Date of initial posting: Tuesday, 11-April-2017... 2:00 PM

Updated posting: Saturday, 31-March-2018... 12:31 PM